ASSEMBLAGE (work in progress #2)

The process of ontographic list-making produces a system of interconnected objects that establishes a nonlinear narrative structure. K-films can be seen to operate in this way*. With each selection made by the user a new list of thumbnail options are presented to them to select from. By navigating their way through the video clips they begin to understand how each video is connected.

Instead of depending on a conventional, linear structure of documentary that hinges upon explicit dramatic cues to progress the user through the narrative (causality), K-films generate a variety of narrative combinations and leave it up to the user to interpret how they are connected. The focus of the user shifts from identifying a logical sequence of information (i.e. a linear understanding of a topic) to a more poetic, holistic understanding that emphasises the connections between each piece of information (nonlinear).

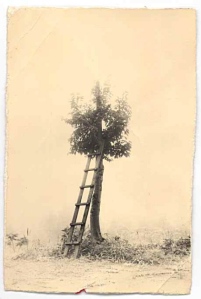

In Placing the Bend for example, why is footage of a tree trunk connected to footage of moss, which in turn is connected to footage of the Yarra river?

The interest becomes more about why these different objects are connected, not what the objects are doing. The actions of the objects bares no consequence to the overall narrative within a Korsakow film. There is no direct cause and effect enacted by the objects within each clip of footage. We assemble the information in a different manner to traditional modes, drawing meaning from the implicit connections between each video clip rather than the actions played out within the video clip.

Instead of focusing upon what has passed, we are constantly searching for what will come next. In this way, we are “future-geared” to search and identify how the upcoming information is tied to the present information. Unlike a conventional, linear narrative that bases it’s progression on the past events that have occurred within the assemblage of information, a nonlinear poetic narrative works in a way that promotes a proactive investigation to discover the connections between each piece of information.

We may not be able to comprehend these connections until we have viewed the interactive documentary several times. The connections between a tree trunk, moss and a river may only become apparent on the third or fourth time of engaging with the documentary. In this example, vertical objects are linked with circular, which in turn are connected to horizontal objects. One reading of these connections may be exploring the unity between flora and the river within the BOI. Another reading may relate to the juxtaposition between slow and fast rates of change within that region.

The connections we find from exploring the “contours” (Bernstein, 22) of the documentary become a strong thematic point in the overall narrative, revealing the purpose of the assemblage and how it is to be read.

The level of engagement an interactive documentary enables not only alters our temporal-orientation in reading a narrative, but as Manovich explains, adjusts our focus from understanding narratives as fixed syntagms to variable paradigms.

Manovich appropriated Saussure’s semiological terms in order to describe the shift from media that was traditionally temporally-focused to New Media that places more emphasis upon the spatial orientation of information. Manovich describes a syntagmatic system as a sequence of elements strung together temporally, whereas a paradigmatic system chooses each new element from an established set of related elements. In this way, Manovich summarises the syntagm as explicit whilst the paradigm is implicit; ‘one is real and the other is imagined’ (203).

For example, when we assemble our impression of the BOI we may think back to how we originally experienced it. This may begin with driving into the region on an unsealed road, walking down an unkempt trail into a densely forested area, steadying ourselves as the trail descends before coming across the river. This is a syntagmatic system of events, recollecting the chronological sequence of events in relation to how we experienced it. A paradigmatic recapitulation of events would be nonlinear in construction, emphasising the spatial dynamics of the region; these types of trees are within this region; there are different types of trails throughout the region that look like this, and this. And so on.

Paradigms can be seen as lists whereas syntagms can be seen as timelines. For quite some time media has been presented in a fixed, linear syntagm that imposes a diachronic assemblage of information. With the advent of New Media, Manovich explains that the paradigmatic structure has been given a new lease of life. Many interactive documentaries offer an opportunity to explore the information presented paradigmatically (spatially) rather than syntagmatically (temporally). This is the main difference between webdocs and idocs. The former appropriates it’s structure from the traditional style of documentary: a linear narrative that allows “exit points” to multimedia, contextualising information that deepens the users understanding of the topic. The latter draws upon the autonomous functionality afforded by search engines and encyclopaedia’s that allow the user to navigate freely through an spatial array of information.

Here are two examples. The first is the webdoc Prison Valley (2009), second is the idoc Water Life (2009).

Korsakow functions in quite a different way to Manovich’s syntagm and paradigmatic structuring. The algorithms embedded within the program react to user interaction by generating new assemblages of clips based upon the keyword associations you have made at the projects conception.

These keywords offer a different style of paradigm, enabling sparse distributed connections rather than connections made from the similarities of each video clip. Likened more to the functionality of a homograph, K-films operate by linking a variety of information under the one keyword. Keywords in K-films, like a homograph, represent the unification of a variety of meanings.

A homograph is one term that means a variety of things. For example, the word “close” means either to “close a door” or “become close to another.” The term “wave” is a physical gesture (i.e. “I waved goodbye to them”) as well as an environmental occurrence (i.e. “waves crashing on the shore”).

The author has the ability to compose any keyword within Korsakow and determine what it is linked to. The author may decide to link the keyword “vertical” with everything that grows upwards or is physically portrayed as vertical within the BOI. However, poetic assemblages within Korsakow generally work best when a keyword does not function in such a literal sense. For example, instead of linking a tree trunk and a cliff to the keyword vertical, the author will form a much more interesting K-film if he chooses the word “rough” or “tower.”

In this instance, an unpredictable narrative structure will emerge as the user jumps from quite disparate and seemingly incongruous video clips of “rough” things or depictions of “towers”. The less logical and literal the keywords are the more poetic the narrative structure will become, allowing the user a variety of ways to interpret the assembled narrative.